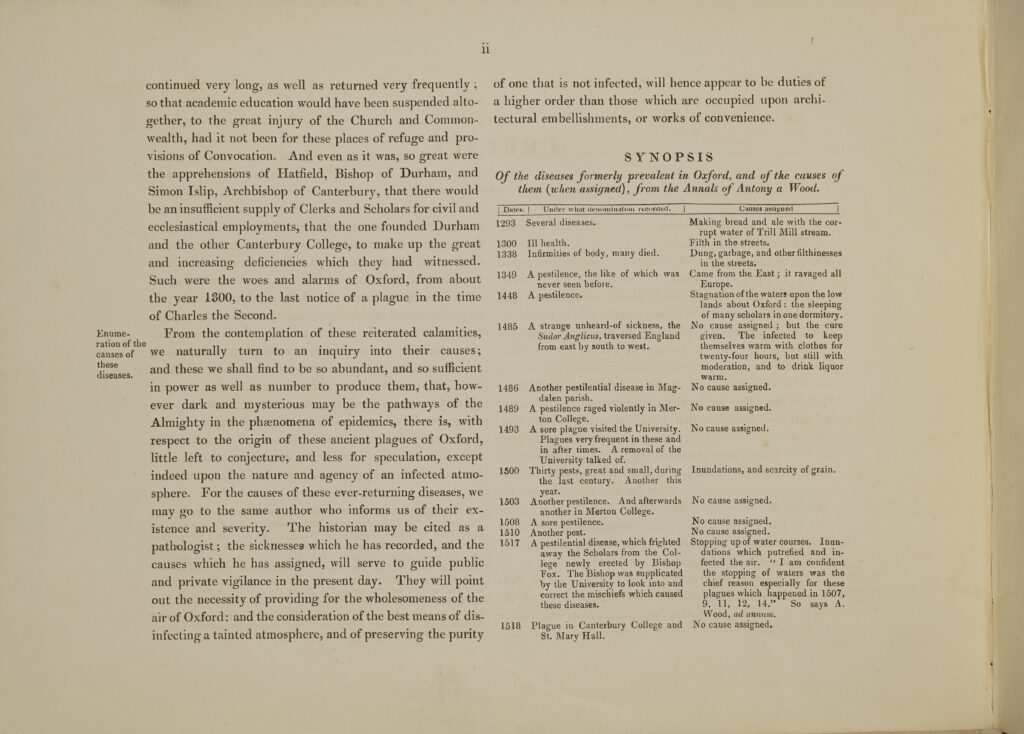

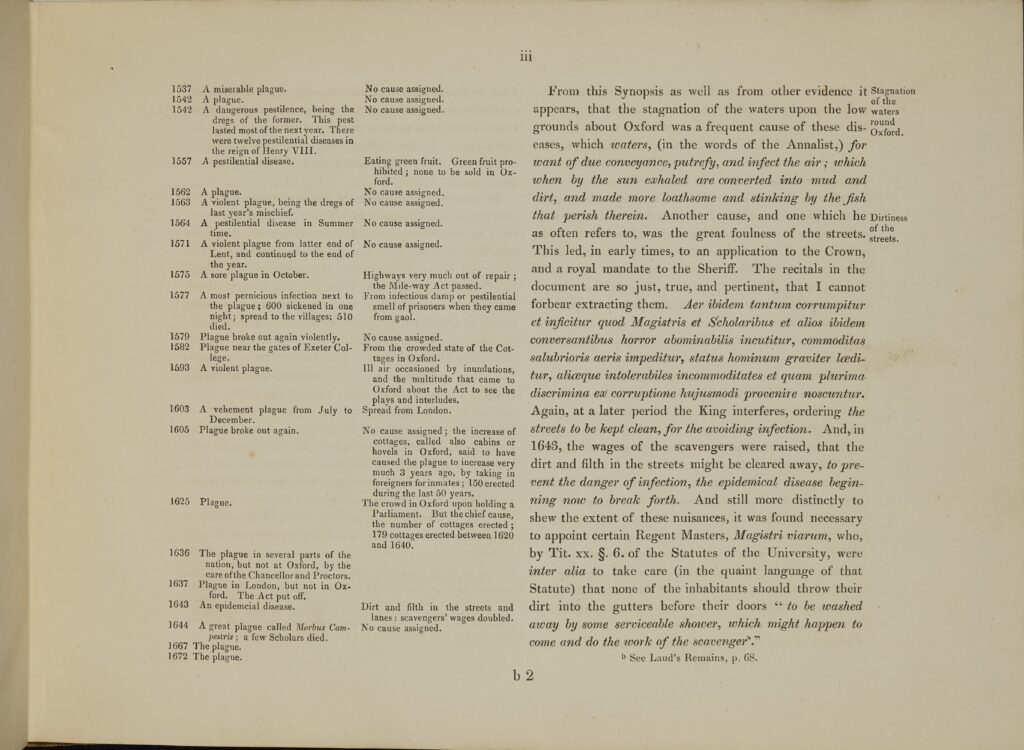

Oxford grew rapidly in the 19th century with increased industrialisation and rural migration. This further exacerbated existing overcrowding and resource constraints, while the two river systems of Oxford contributed to the spread of infectious disease.

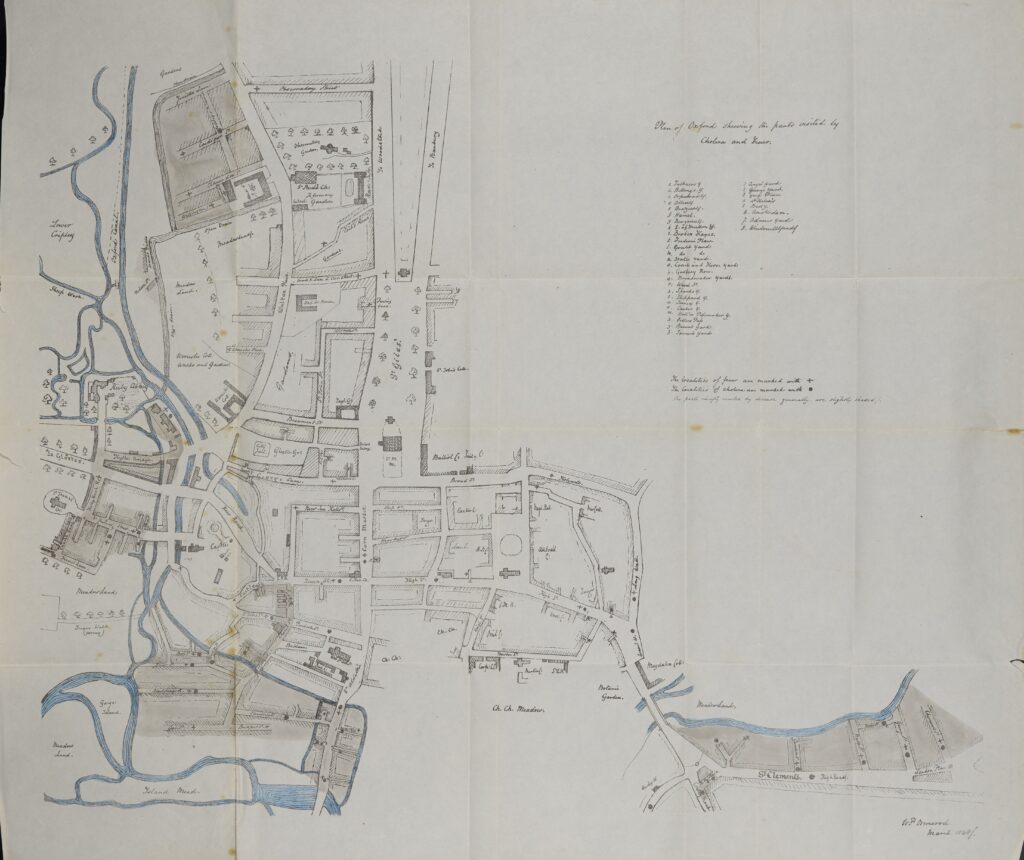

In the 19th century, there were three cholera epidemics (1832, 1849, and 1854) and three typhoid epidemics (1874, 1875, and 1879) in Oxford. As disease maps from the period show, most infections were in impoverished areas, particularly those close to dirty river systems.

During the first cholera epidemic, William Gunstone, a butler at Magdalen, lost his wife, two adult daughters, and his servant to cholera. In 1856, Henry Bird, then a twelve-year-old chorister at Magdalen, died of typhoid fever, being buried with great ceremony in the Holywell Cemetery to the north of the college estate.

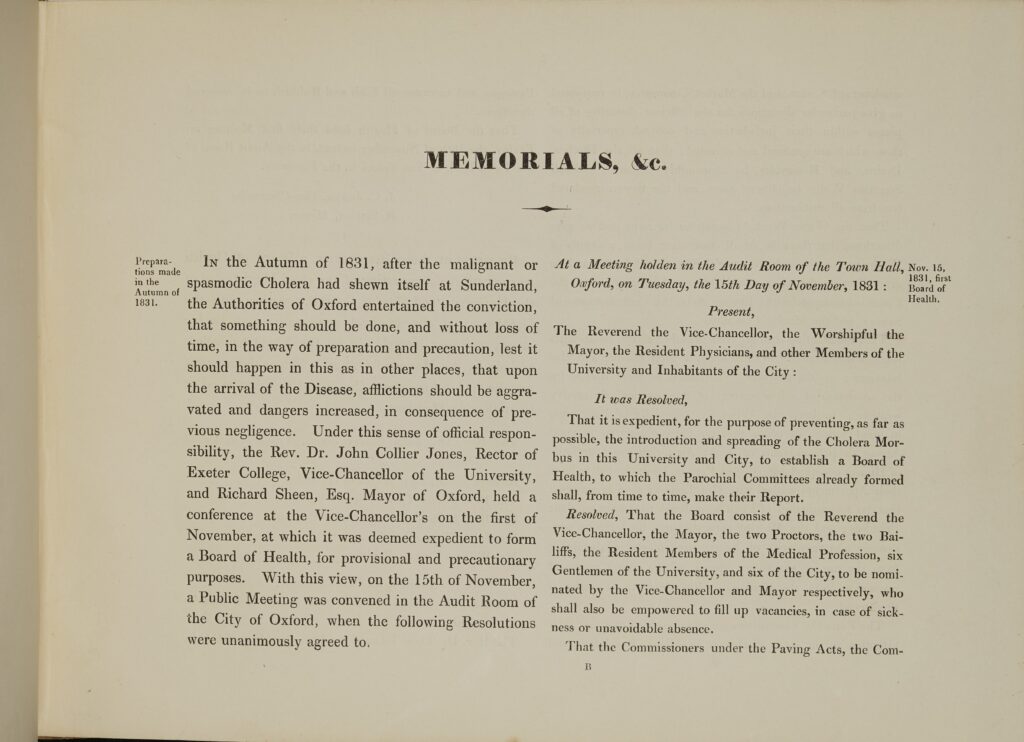

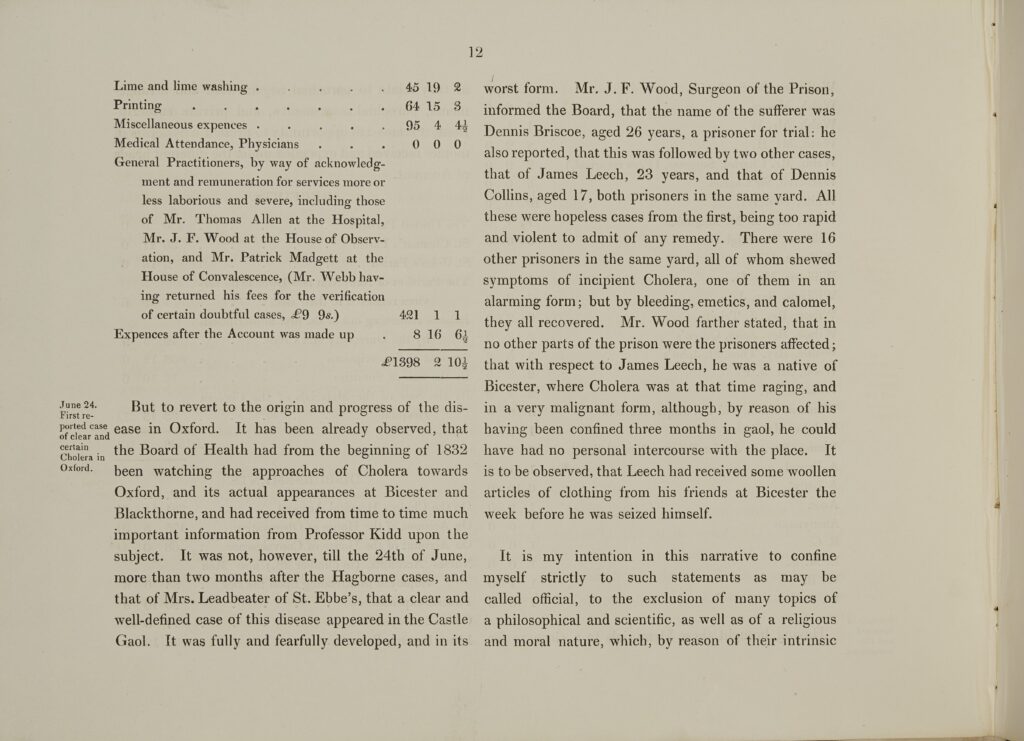

In response to the 1832 cholera epidemic, a Board of Health was founded in Oxford. It issued a notice in advance of St Giles’ Fair that advised residents to ‘beware of mixed, crowded, and unknown Companies in the distempered atmospheres of Booths, Show Rooms, and Canvas or Boarded Apartments’. This period also saw the establishment of a cholera hospital within Oxford, to which Magdalen contributed funds in November 1849.

In the later 19th century, miasma theory was gradually replaced by germ theory. The bacterium that causes cholera was identified in 1854 and the typhoid bacillus in 1880. The emphasis of early public health efforts on improving sanitation did not go away, however, as it was quickly recognised that both were transmitted by contaminated water and food.

On the Sanitary Condition of Oxford

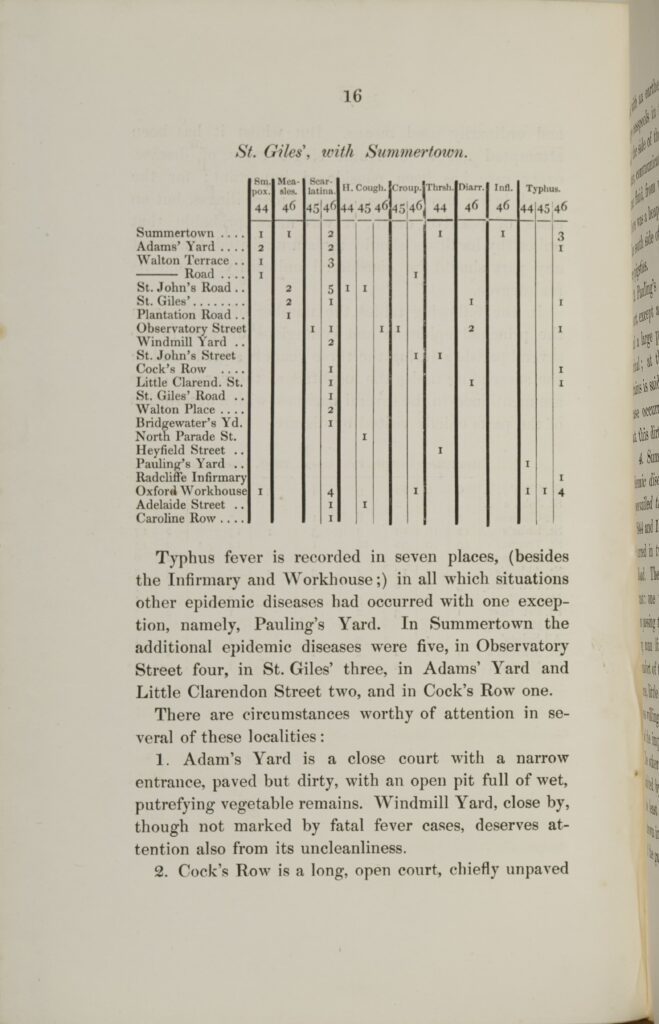

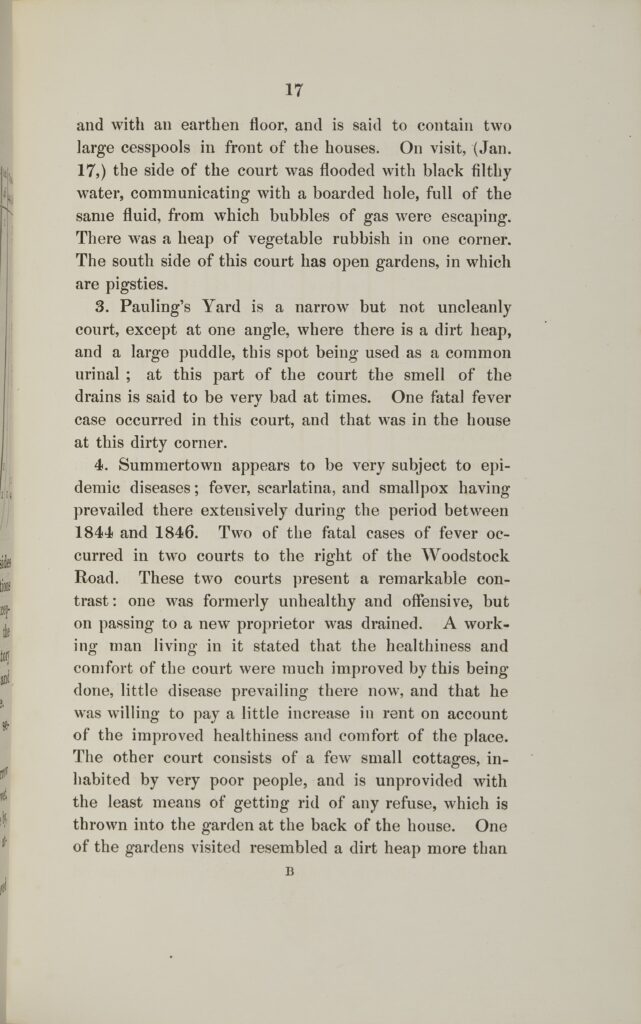

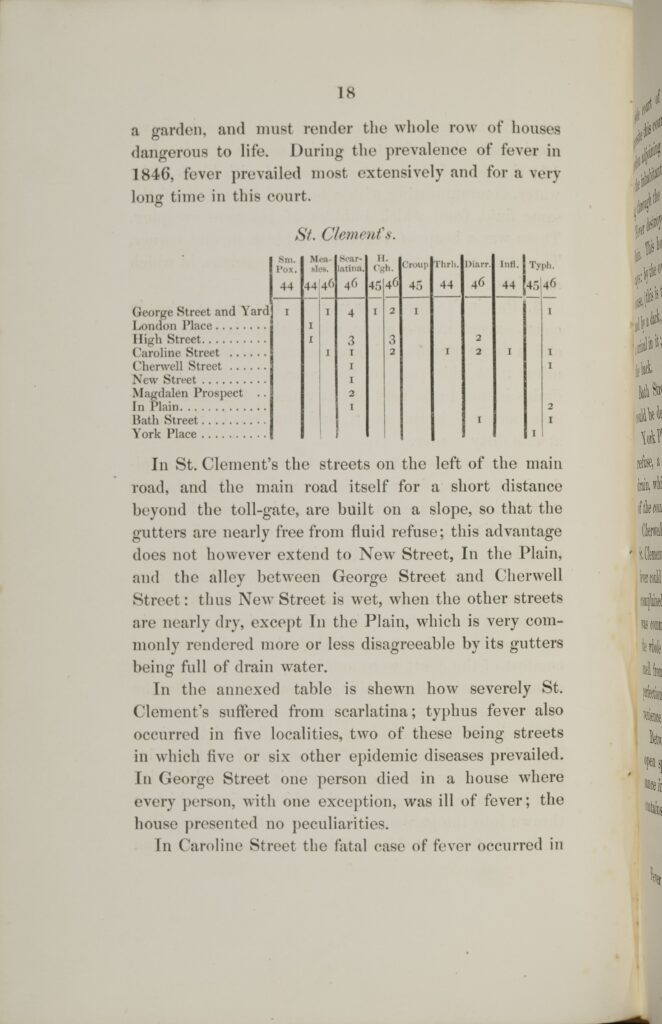

W.P. Ormerod (1816–60) was a physician at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford. This tract contains his analysis of cholera outbreaks in Oxford. Ormerod collected his data as the Oxford City Council discussed implementing the 1848 Public Health Act.

Ormerod’s map uses dots and crosses to mark the presence of cholera and fevers in central Oxford, and shading to point out areas of the city that were more unsanitary, including the region that now houses Magdalen’s Waynflete Building.

Predating John Snow’s cholera maps of London, Ormerod’s map likely would have been more famous in the history of medicine if he had not still subscribed to miasma theory.

Magdalen College Library, a.18.18

Malignant Cholera in Oxford

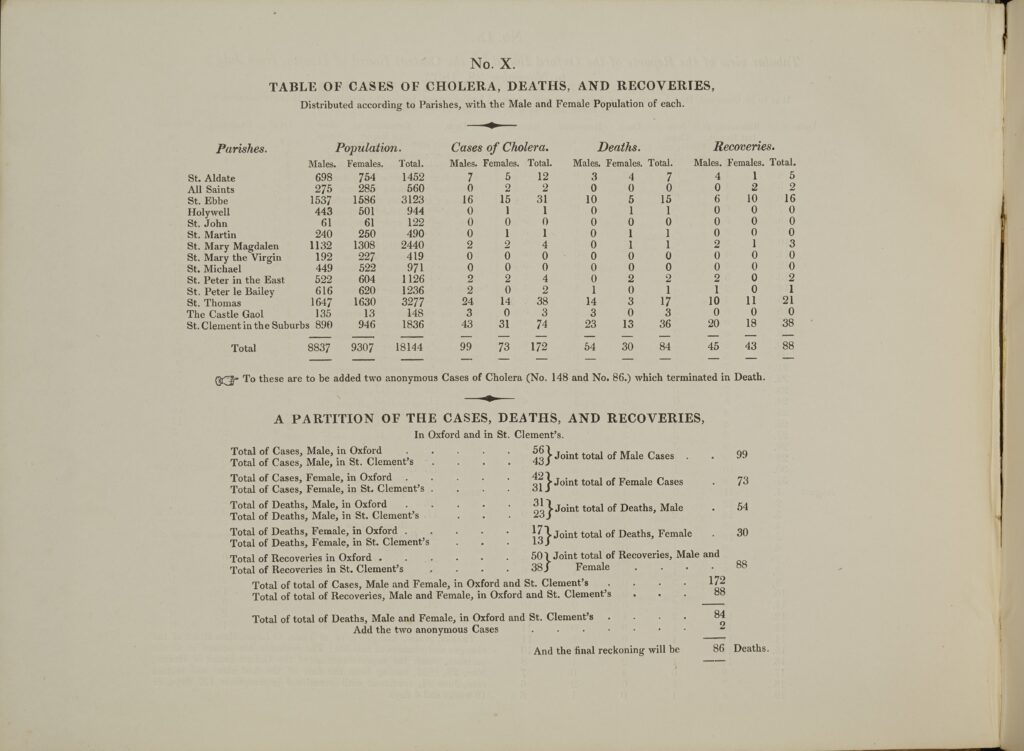

Vaughan Thomas (1775–1858) was an Anglican clergyman and chairman of the Oxford Board of Health in the 1830s. This pamphlet discusses the nature and incidence of cholera in Oxford.

Thomas drew on biblical passages to support his advocacy of a welfare state, in which public health authorities had paternalistic responsibility. He offered religious interpretations of cholera outbreaks, but he also pointed to overcrowding, bad drainage, poor ventilation, and dirty streets as causes.

Thomas gifted this copy of his tract to the then President of Magdalen, Martin Routh (1755–1854).

Magdalen College Library, r.12.14

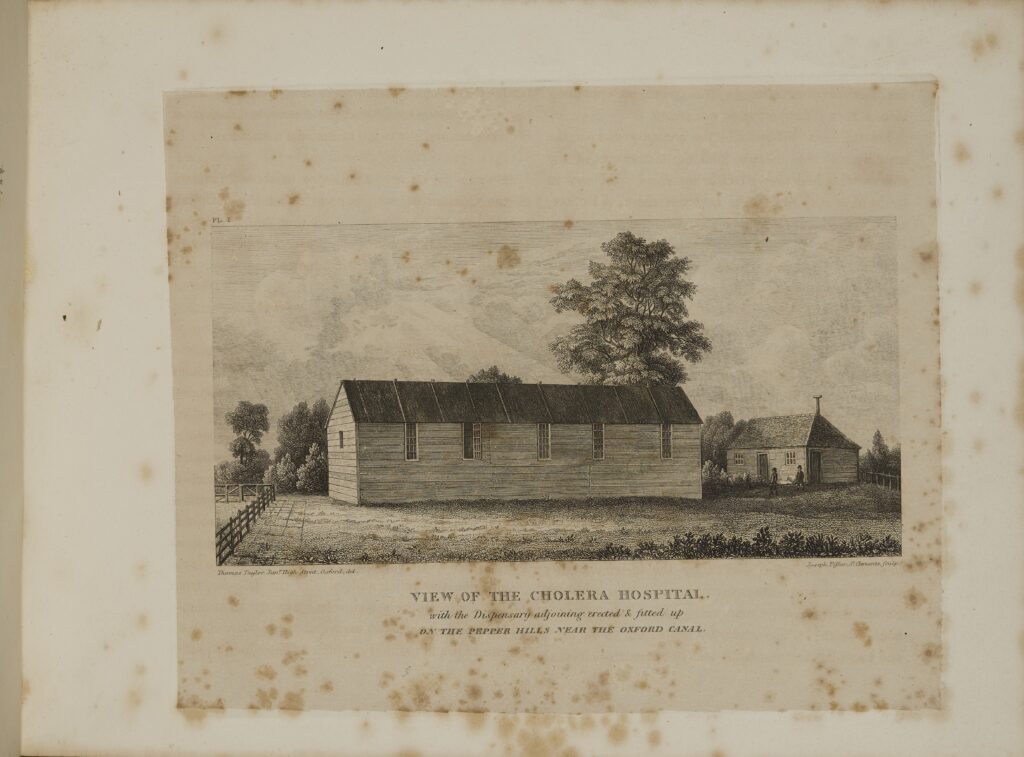

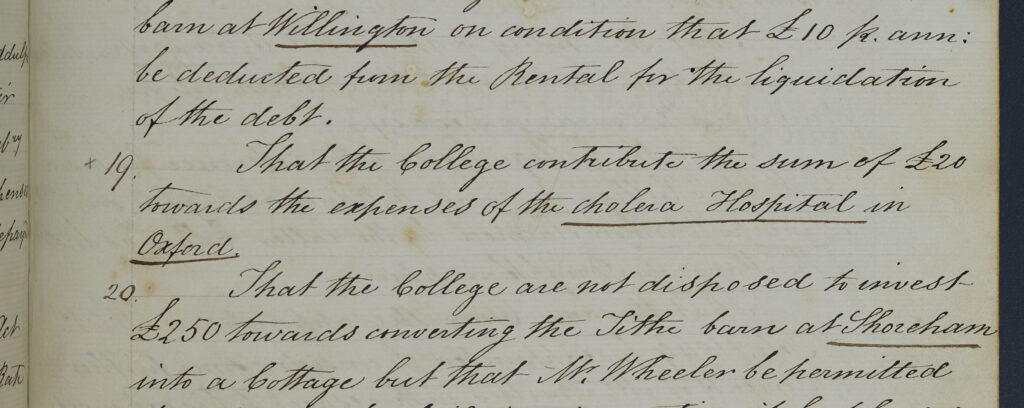

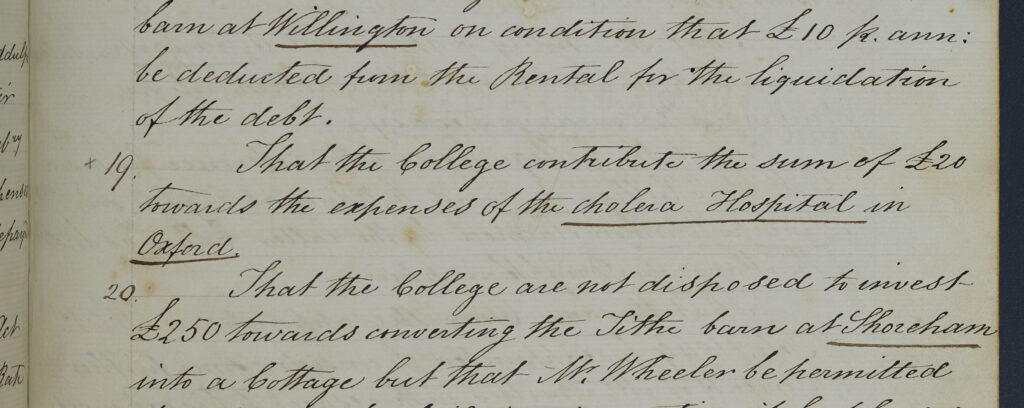

Cholera Hospital

On 7 November 1849, the Governing Body of Magdalen College agreed to contribute £20 towards the cholera hospital in Oxford.

The hospital itself was based at Pepper Hill, near the canal, and was originally opened in response to the cholera epidemic that swept through Oxford in 1832.

Magdalen College Archives, CMM/1/4

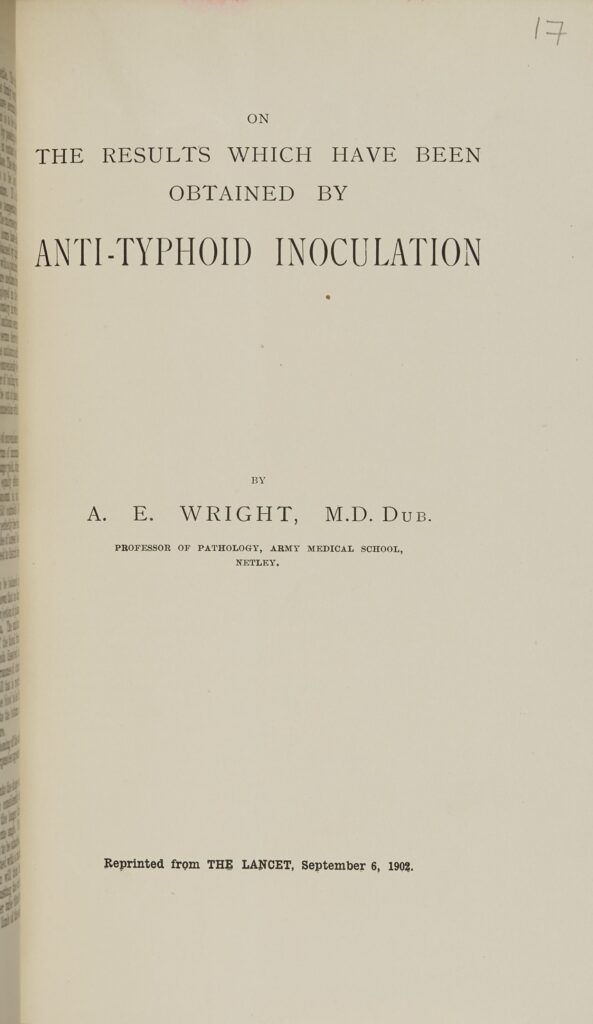

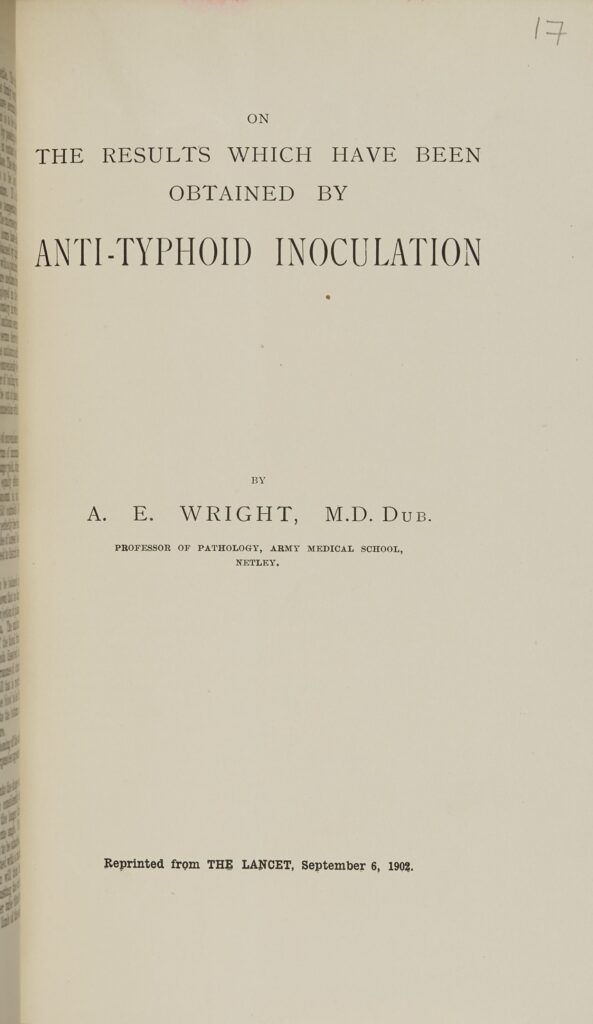

Anti-Typhoid Inoculation

Sir Almroth Wright (1861–1947) was a bacteriologist and immunologist famous for developing an anti-typhoid inoculation.

Several researchers had been working on a vaccine in the 1890s and early 1900s. Instead of using a living, attenuated vaccine, Wright used a heat-killed bacilli vaccine, which he argued was much safer but just as effective.

During trials of his vaccine amongst staff at a Dublin asylum, none of those vaccinated became infected with typhoid, despite attending to typhoid patients, while 16 of the 120 unvaccinated staff developed infections.

Magdalen College Library, 89.M.13(17)

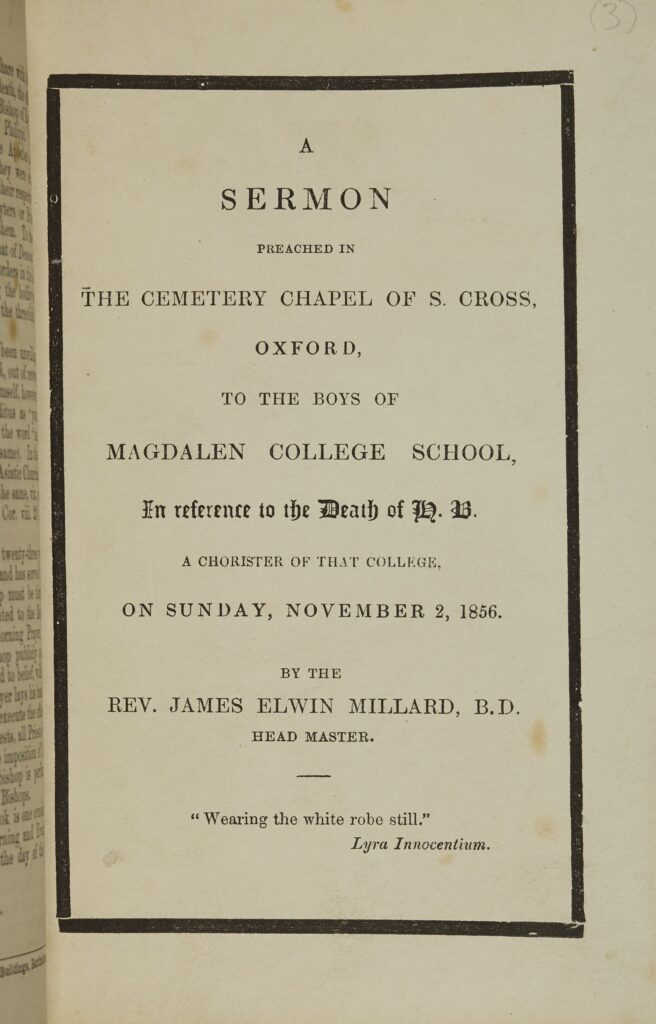

Funerary Sermon

This sermon was preached on 2 November 1856 by James Elwin Millard (F 1853–94) at the funeral of Henry Beaumont Coles Bird, who had been a chorister at Magdalen. Bird had died earlier that year, aged just 12, of typhoid. Millard, who had himself been a chorister, was then serving as Master of Magdalen College School (1846–64).

Taking the death of King David’s son as his theme (2 Samuel 12), Millard sought to persuade the other young school boys present that they should see in Bird’s untimely passing an event that brought them closer together as a community and to God.

Magdalen College Library, S.19.7

Tomb

Henry Bird was buried with great ceremony in the St Cross Cemetery, just to the north of the Magdalen estate. His mother entrusted the design of his tomb to prominent architect J.C. Buckler (1793–1894), while the figure of Henry was carved by Thomas Earp (1828–93), best known for his reproduction of the Eleanor Cross at Charing Cross, London. Bird’s tomb was restored in 2017.

Photograph © Dr Richard Allen

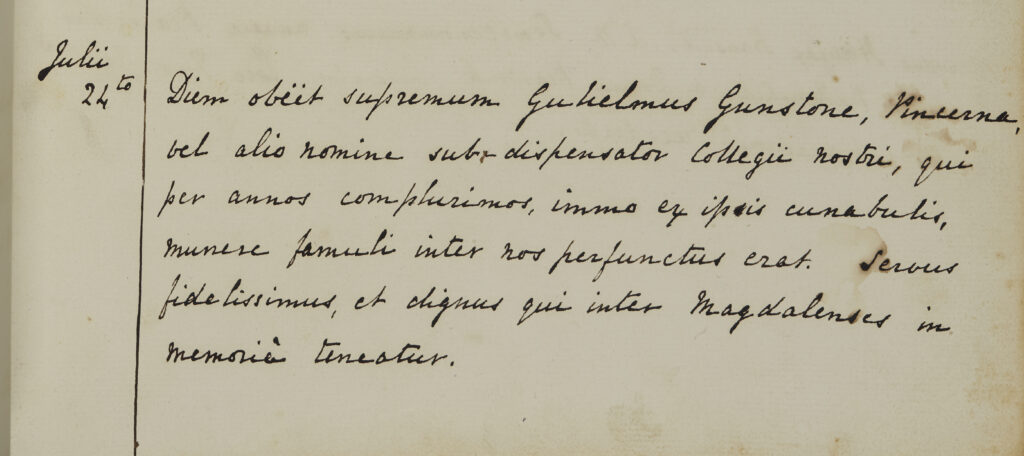

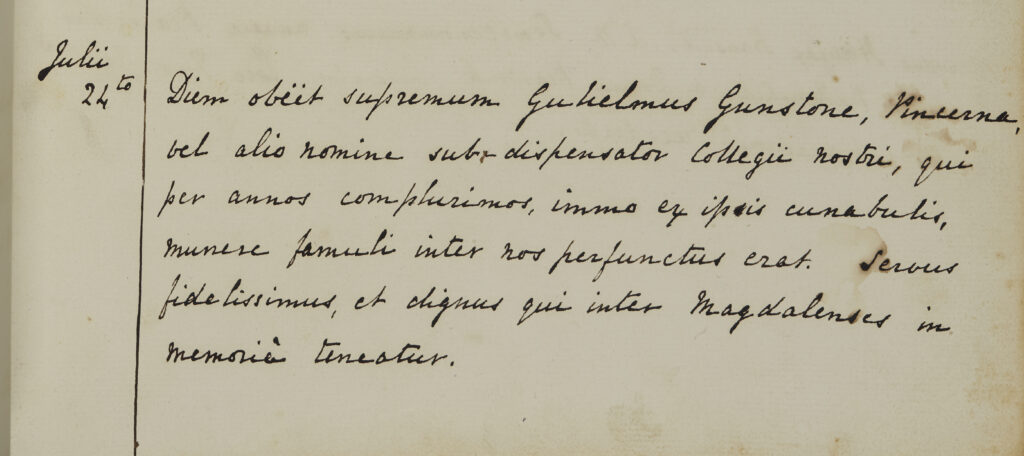

Register

This register entry records the death of William Gunstone, a college butler, in July 1842. Gunstone lost three members of his family to the cholera pandemic of 1832.

Magdalen College Archives, VP1/A3/1, p. 234

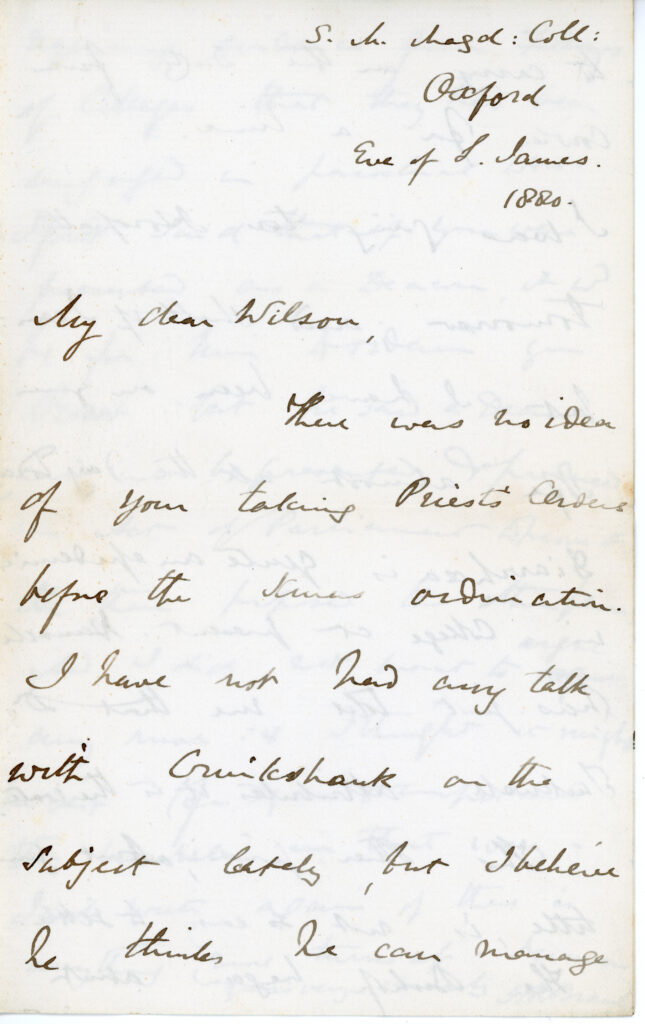

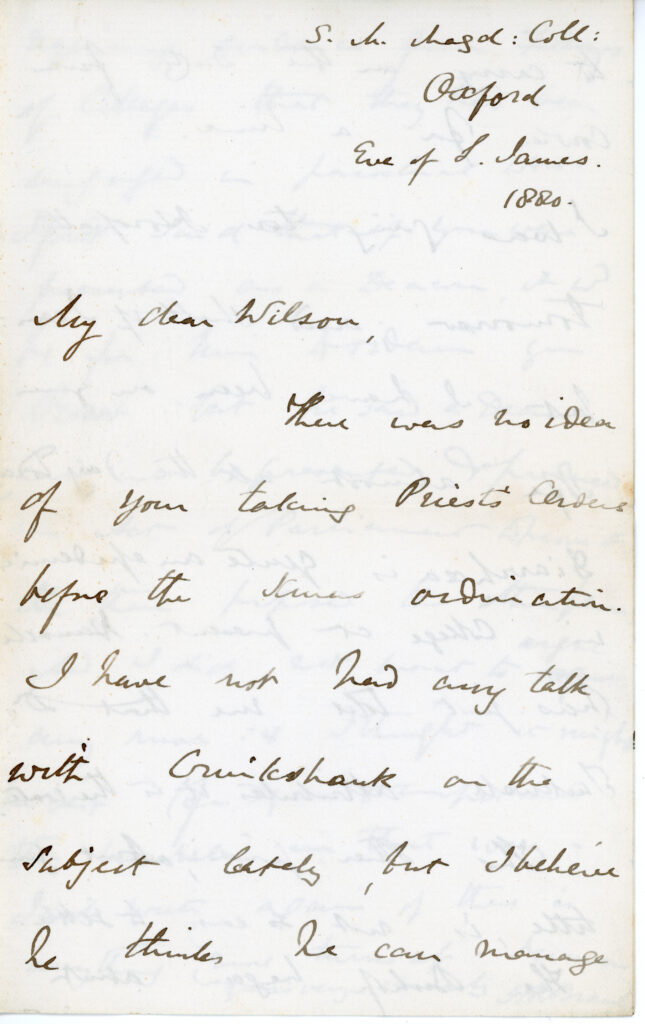

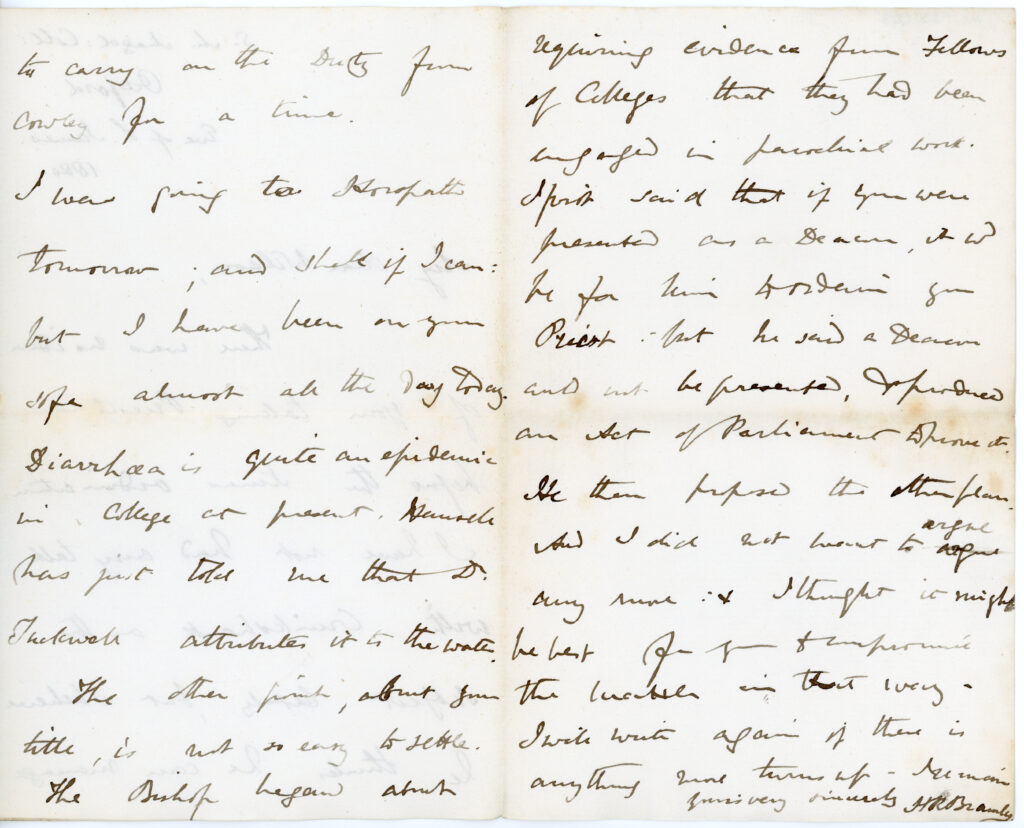

Diarrhoea Epidemic

In this 1880 letter, H.R. Bramley (F 1857–1908) reports on an ‘epidemic’ of diarrhoea at Magdalen, showing localised outbreaks of disease could still occur, despite wider sanitary improvements.

Magdalen College Archives, F23/C2/3

Sir John Burdon Sanderson (1828–1905)

John Burdon Sanderson was an experimental pathologist whose work contributed to the uptake of the germ theory of disease in Britain. Burdon Sanderson was Fellow of Magdalen from 1882 when he was appointed the first Waynflete Professor of Physiology, a controversial appointment due to his use of animal experimentation.

In the 1850s and 1860s, Burdon Sanderson studied outbreaks of diphtheria, cattle plague, and cholera. He undertook experiments to test the communicability of the latter by feeding animals with ‘extremely minute quantities of the morbific material’.

In 1871, Burdon Sanderson noticed that Penicillium inhibited bacterial growth. He worked closely with his wife, Ghetal Herschell (1832–1909), with whom he co-authored sanitary reports. He remained a fellow of Magdalen until 1904.

Magdalen College Archives, F/X, p. 10

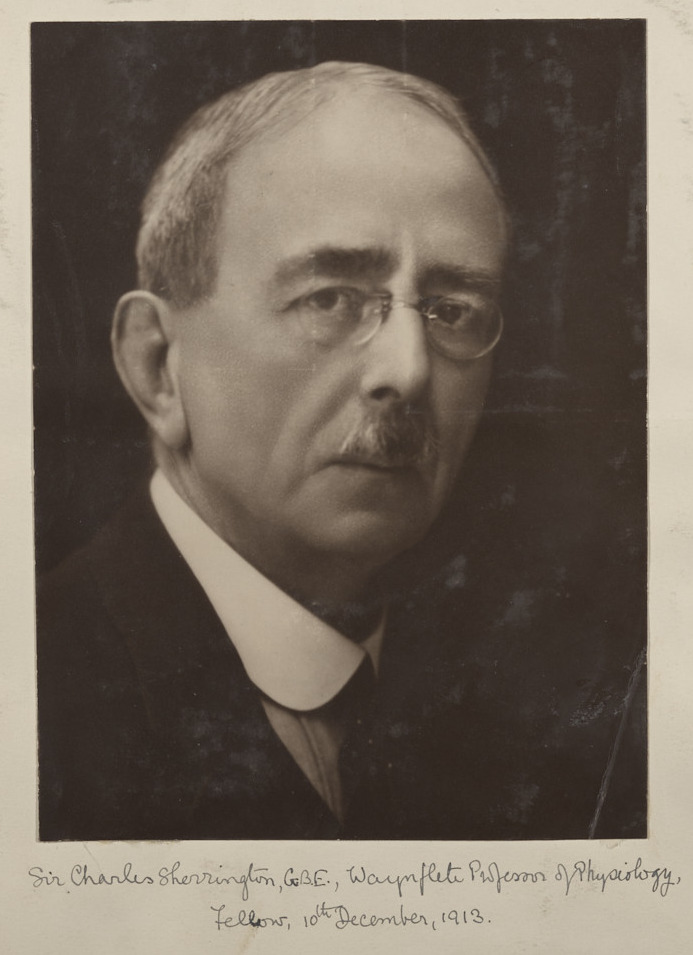

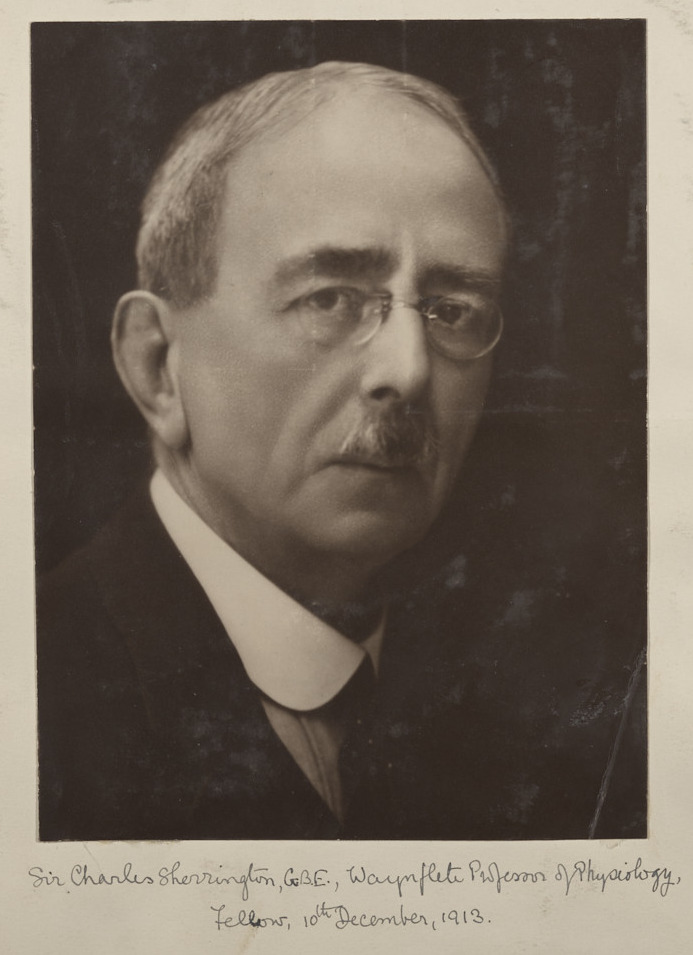

Sir Charles Scott Sherrington (1857–1952)

Charles Scott Sherrington was Waynflete Chair of Physiology at Magdalen from 1913 to 1936. As well as making significant contributions to neurophysiology, Sherrington also studied cholera.

In 1885, he travelled to Toledo, collecting samples of cholera bacteria from the bodies of the recently deceased. While in Spain, he investigated the claims of a new cholera vaccine, concluding that it was largely ineffective. In 1886, he travelled to Venice to investigate another outbreak. He soon took his samples to a laboratory in Berlin for further study, after which he worked with the famous microbiologist Robert Koch.

Sherrington won the Noble Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1932. Named in his honour, Magdalen’s Sherrington Society hosts distinguished speakers in the medical sciences.

Magdalen College Archives, O1/P1/1, p. 76